In November, I was a guest of the Research Excellence Cluster Global History of Anticolonial Thought at the University of British Columbia (UBC) in Vancouver. This is an interdisciplinary group of scholars and students at UBC who are investigating the multitude of ways that anticolonialism has taken shape across the globe in response to four centuries of European imperialism and settler colonialism. Their work starts from the premise that a global approach allows them to unearth the exchange of ideas and the connections of solidarity across cultures, places, oceans, and eras that are and have been vital to the evolution of anticolonial thought. Though the remit of their research is broader (and their group much larger), there is lots of potential synergy with the history of peace movements & decolonization here!

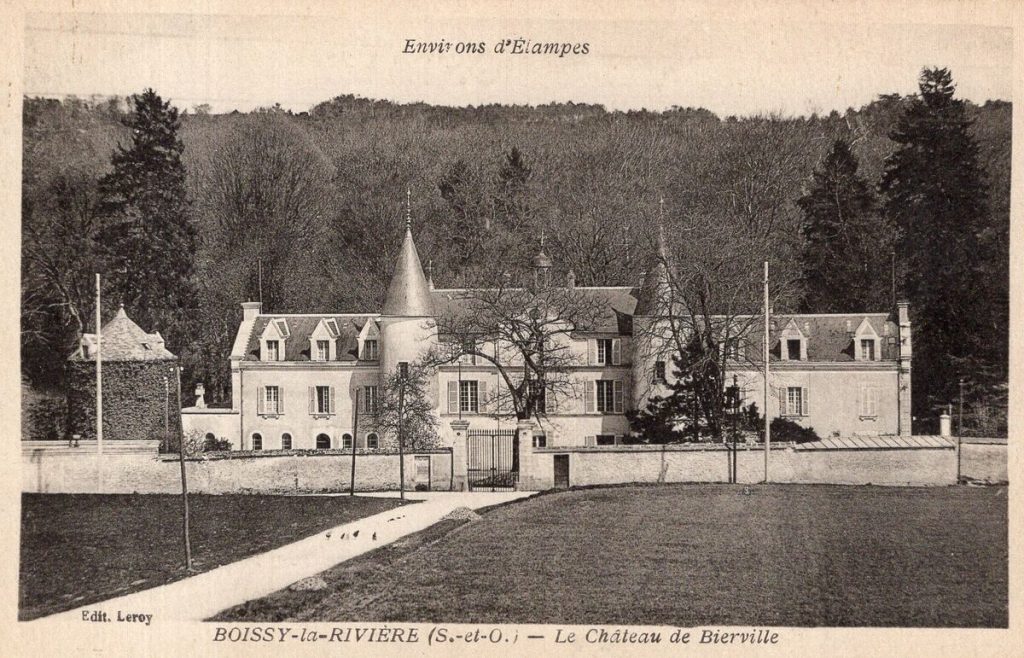

I gave a research talk on a rather ephemeral partnership between a small group of anticolonial activists in Paris, and a much larger group of European pacifists, who came together at the Congrès démocratique international pour la paix in the tiny French village of Bierville in 1926. The conference was spearheaded by the French Catholic intellectual and politician Marc Sangnier, who hosted the conference at his country estate in the commune of which he was the recently elected mayor. In keeping with Sangnier’s political goal of Franco-German reconciliation, the vast majority of delegates was European, and around twenty percent of the delegates were German pacifists – not an easy feat to pull of just a few years after Versailles! That was on purpose: Sangnier wished to create a public demonstration, with much spectacle, of the popular support for cultural demobilization and for the process of reconciliation that had become policy through the Locarno Accords. Among the 5000 participants were 5 – five! – Asian participants. Despite being in this overwhelming minority, one of them, K.M. Panikkar, took to the main the stage and thundered the following words over the crowd:

All have noticed how the European is hated throughout the East. Why? Is it because the Asiatics – the Chinese, the Indians or the Egyptians – are a barbarous people? No; but because all over Asia we feel we are being held down mercilessly by the force of superior arms. Is this accumulation of hatred, which, though we may deplore, we cannot deny, an asset for peace, or is it its greatest enemy? If you wish for peace, your first work should be to eliminate the causes which make Asia hostile towards Europe, and to dissolve this vast accumulation of hatred.

Panikkar, of course, was talking about the European colonial occupation of Asia. He spoke on behalf of this five-person Asian Delegation and as its representative from India. The other four were Duong Van Giáo, who represented Indo-China; Alimardan Bey Topchubashov for Azerbaijan, Tung Meau for China, and Mohammed Hatta for Indonesia. The delegation succeeded in having two motions entered into the conference record: that the global economic crisis of the 1920s could not be solved without “Asia’s” help – help that would not be possible as long as “the Asian peoples” were not free to work for the cause of reconstruction, civilization, and peace. The second motion was directly reflective of Panikkar’s long and fiery speech, that “considering that universal and permanent peace is impossible without the liberation of oppressed people, the conference mandates its national delegations to work in their respective countries for the liberation of these people.” If Sangnier had meant for the Bierville conference to show popular support for Franco-German reconciliation, to the Asian delegation, these two resolutions evidenced popular support for the self-determination of all peoples.

The first implied that “reconstruction, civilization, and peace” were not possible without an end to colonial occupation. It also linked Asia’s ability to advance economically to the ability of Asians to chart their own political course. Given the demographics of the Bierville gathering, which historian Gearóid Barry has characterized as “Catholic-inspired political ecumenism”, this was indeed surprising. On the one hand, Sangnier’s “ecumenism” had made space for a sizeable presence of socialists, in whose circles the colonial question was more regularly debated. On the other, the motion actually went further than those of the organizations from which they hailed – none of which, by 1926, had reached a consensus on the issue. Some, like the international federations of trade unions, wouldn’t get there until after 1945. The second motion was even more far-reaching: it framed the “liberation of oppressed peoples” as a prerequisite for world peace and called the conference delegates to action in order to achieve that liberation.

Pacifists more broadly had to contend with the fact that action for decolonization would require working together with anticolonial organizations, many of which were not built on pacifist ideals and did not reject the idea of armed revolution. The question whether working together with such movements was possible and if so, to what extent, was a contentious one. This issue became even more pronounced, and this type of alliances more short-lived, as some decolonization processes turned violent in the postwar decades. The issue was equally difficult for anticolonial activists for whom the first priority was not world peace but decolonization, and who did not wish to exclude any modes of protest a priori. Hatta, for instance, tried to pre-empt the critique that participating in a pacifist conference like Bierville compromised the “revolutionary foundations” of the Indonesian student movement. Invoking an imaginary detractor, he wrote in Indonesia Merdeka [Free Indonesia]: “No! We have made use of this opportunity to show these Western democrats the inextricable link between humanitarian principles and the revolutionary struggle for national independence.” The pattern of a briefly successful but ultimately temporary partnership seen in Bierville, would repeat itself often in the decades to come.