by Carolien Stolte

In L’Âge Atomique (Musée de l’Art Moderne, Paris), the world responds to the sense of instability that was introduced to it from the moment it became known that the atom was not, in fact, its smallest component part. In this perspective, Rutherford’s discovery of subatomic particles functions as the “big bang” from which all artistic engagement with the nuclear emerges. This has enabled the curators to span the earliest years of the twentieth century – Kandinsky describes how the divisibility of the atom shook his soul and made him feel as if the world itself was collapsing – to those of the twenty-first, in which the insecurities associated with the nuclear are different, but no less fundamental.

This broad setup has a number of other advantages. It allows the viewer to see even the most well-known artists in a new light. For instance, Salvador Dalí had a “nuclear mysticism” phase, which went as far as presenting a new interpretation, for the atomic age, of the Immaculate Conception to Pope Pius XI. The broad setup also makes space for the fact that, given the many twentieth-century shifts in global power and resource inequities, responses to the nuclear are historically and locally contingent: it means different things in different places.

At the same time, the thematic organization of the exhibition does not allow for as much exploration of the latter as I would personally have liked. Most of the inclusion of the decolonizing world concerns sites that were the unfortunate subject of nuclear tests, programs, or crises. They figure much less prominently as spaces that responded to the nuclear age autonomously. One such autonomous response that might have been included is the specific antinuclear manifestation of Afro-Asian solidarity – a movement in which myriad artists were involved.

The exhibition does have a fascinating section entitled “nuclear colonialism”, which centers on indigenous protest against nuclear testing in areas that are unjustly framed as “empty” territory. But nuclear colonialism’s opposite – antinuclear anticolonialism – is harder to capture as a movement that focuses not on specific lands, but on a nuclearized power dynamic that threatens all lands. Antinuclear anticolonialism, in the final instance, is a global peace movement. And while peace movements do figure in the exhibition, projects rooted in global solidarity remain absent.

Interestingly, this antinuclear anticolonialism has a somewhat counter-intuitive mirror image that might, for present purposes, be defined as “nuclear internationalism.” This nuclear internationalism, the idea that nuclear energy might point the way to global peace and prosperity, suffers from an unfortunate physical location in the exhibition. It is paired with a very different kind of nuclear optimism: that of American self-congratulation after operation Crossroads, the first tests conducted in the Marshall Islands. Given that the “Operation Crossroads Cake,” shaped like the radioactive seawater-geyser that the test produced, is not even the most bewildering photo on this wall, the rather muted display on civil nuclear energy on the wall opposite is comparatively easy to miss. Nuclear weapons will always be more spectacular, literally and figuratively, than nuclear energy. Still, the display on “nuclear internationalism” as peace thinking is worth unpacking.

while Admiral Frank J. Lowry looks on, 1946.

On 8 December 1953, US President Dwight Eisenhower declared before the UN General Assembly: “The atomic age has moved forward at such a pace that every citizen of the world should have some comprehension, at least in comparative terms, of the extent of this development of the utmost significance to every one of us. Clearly, if the peoples of the world are to conduct an intelligent search for peace, they must be armed with the significant facts of today’s existence.” Eisenhower’s Address on Peaceful Uses of Atomic Energy became known colloquially as the “Atoms for Peace” speech. It launched the eponymous “Atoms for Peace” program, which supplied equipment and, indeed, information, to schools, hospitals, and research centers throughout the world. As a move towards international transparency, rather than secrecy, it made it possible to imagine things like the International Atomic Energy Agency (1957) and the Nonproliferation Treaty (1968).

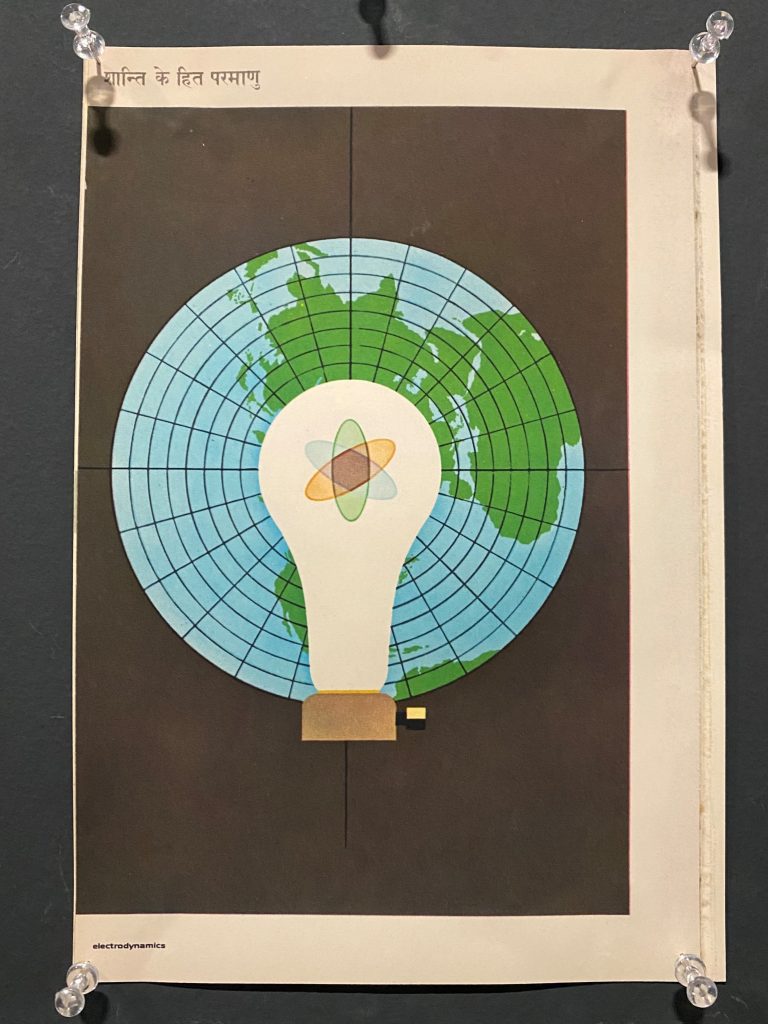

India was a major beneficiary of the Atoms for Peace program, and a poster of its local campaign Shanti ke hit parmanu is pinned to the exhibition wall. Despite its simplicity, it offers an interesting visual. The representation of nuclear energy as a lightbulb with swirling particles is unambiguous enough. But the orientation of the map is not that of the United Nations flag under which Eisenhower delivered his Atoms for Peace speech. The UN flag is centered on the north pole, but otherwise oriented in the traditional western style. Shanti ke hit parmanu has Afro-Asia prominently visible, with the Indian peninsula sticking out almost due north. The Americas, meanwhile, are almost fully hidden underneath the lightbulb, as is northern Europe.

Indian peace advocates were active in all iterations of the peace movement, from religiously inflected pacifism to the left-leaning World Peace Council, and from ashram dwellers to the officials who organized as Parliamentarians for Peace. But Atoms for Peace, despite its name, was on a different historical trajectory. In several countries, including India, dual-use nuclear plants were used – both successfully and unsuccessfully – to make bombs. Fully internalizing the ambiguity that was inherent and perhaps inevitable in the larger program, India conducted its first “peaceful nuclear explosion” on 18 May 1974, under the code name “Smiling Buddha”. From Indian artists, it elicited both pride and existential anguish.

The very different ways in which Indian artists responded to the 1974 test are analogous to the overall impression which l’Âge Atomique left me: the realization that the world-ordering visions which run through the exhibition include both nuclear optimism and pessimism, and that neither sentiment conforms to a straightforward pre/post 1945 chronology or a nuclear have/have-not divide. Even the antinuclear anticolonialism of the decolonizing world and the nuclear internationalism sparked by the Atoms for Peace program were, perhaps, never fully separable. When the Nonproliferation Treaty opened for signing, India declined with the anticolonial argument that it would not sign on to an international regulatory regime that forever fixed global inequality by codifying nuclear “haves” and nuclear “have-nots”. In that sense, the exhibition’s tagline les artistes à l’épreuve de l’histoire – artists put to the test by history – does not apply to artists alone.