by Pratika Dewi

Traditional myths divide the world into two camps in almost every aspect of life, such as war and peace. War appears to be men’s business because militarists used the myth of war’s manliness to define and reward soldiers’ behavior. If war is masculine, peace, as the opposite of war, appears feminine because women who give life tend to oppose war and violence.1 In The Politics of Peace, Petra Goedde uses an ancient story from the fifth century BCE to illustrate the gendering of war and peace. Lysistrata, written by the Athenian poet Aristophanes, emphasized the role of women in ending the Peloponnesian War. The main plot involved women withholding sex with their men until a peace treaty was signed.2 As an outcome, if peace and related issues are referred to as female, then war and related issues, such as nuclear and violence, are referred to as male.

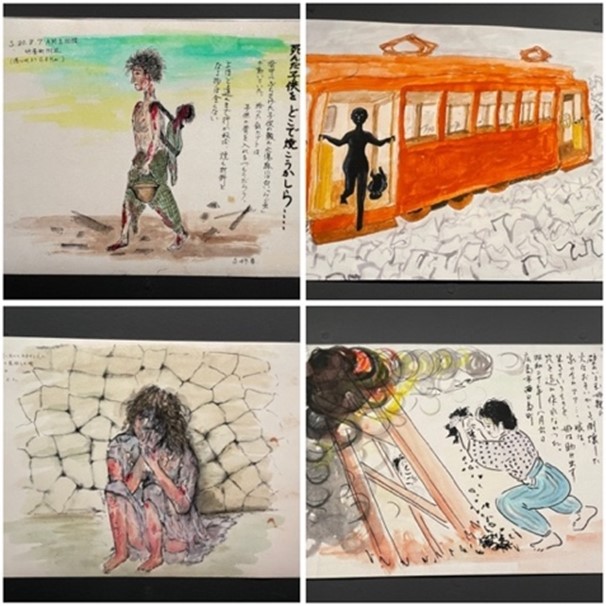

The Nuclear Age Exhibition (in French: L’Âge Atomique) at the Museum of Modern Art Paris invited visitors to explore the creation, use, and consequences of nuclear weapons, including political, social, and physical impacts from various angles. From 11 October 2024 to 9 February 2025, this exhibition encouraged visitors to reflect on nuclear issues through various forms of art expression, such as photographs, paintings, short movies, and art installations. As a visitor who watched Oppenheimer’s film two years ago, this exhibition was easy to navigate because the second panel near the entrance displayed a detailed chronology of the Manhattan Project, which ended with the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombings in August 1945. Then, after this panel, the curators switched visitors to see the opposite conditions, the effects of the atomic bombs, and other nuclear debates after 1945. As I walked past it, I felt sad to see some paintings by Japanese painters portraying women’s conditions following the two atomic bombs. Kazuo Matsumuro, Miyoshi Kukubo, Masato Yamashita, and Chiyoe Kagawa (see picture 1) illustrated women’s expressions as despairing and helpless. In the context of peace and women, I am certain that female positions not only could be seen as victims. I discovered this as I continued to walk deeper into the exhibition.

In her book, Sara Ruddick stated thatwomen’s peacefulness is at least as mythical as men’s violence, and even peace-loving women, like most men, support organizing violence. This statement suited the exhibition plot.3 However, my reflection after visiting this exhibition differs slightly from Ruddick’s. Women’s involvement in nuclear and bomb activities could not be justified solely as their support for the war and violence. This has to do with how these women perceived peace and what propaganda influenced them.

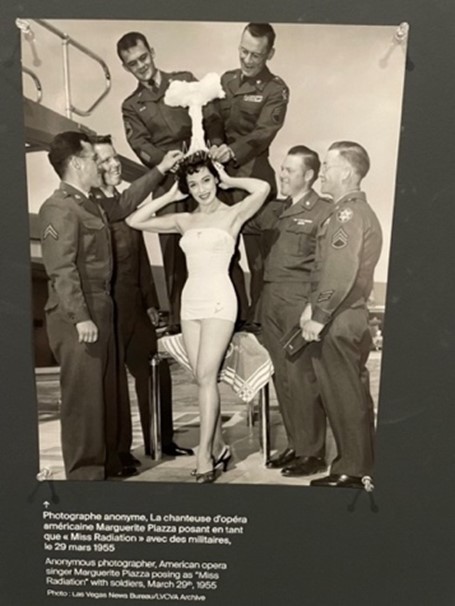

In the panel on The Nuclear Spectacle, a series of photos of Miss Atomic shocked me. Admiral Blandy and his wife smiled as they cut a cake in the shape of an atomic mushroom cloud on 7 November 1946. Next to it, Marguerite Piazza, an American opera singer, proudly wore an atomic cloud crown on 29 March 1955 (see picture 2). A slew of questions popped into my head: Were they aware that the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombs in 1945 killed women and children as well? Even simple, silly questions bother me, such as whether Piazza thought the atomic crown was pretty enough to wear. If I were Piazza, even with zero knowledge of the atomic bomb, I would not wear a strange crown like that. The main question from those pictures is, did those women support the war? If thinking from Ruddick’s deconstruction that women also possibly support organizing violence, the answer is yes. However, under the premise that they were supporters of the United States (US) government, I doubt that they meant to support war. I still see the chance that what those women meant was to support peace. The US propaganda on the atomic bomb as a way of achieving peace made those women believe that they correctly supported peace. These women were trapped in the government-promulgated propaganda of the ‘good atom.’ In consequence, in the eyes of pacifists, for instance, they seemed to support war and violence.

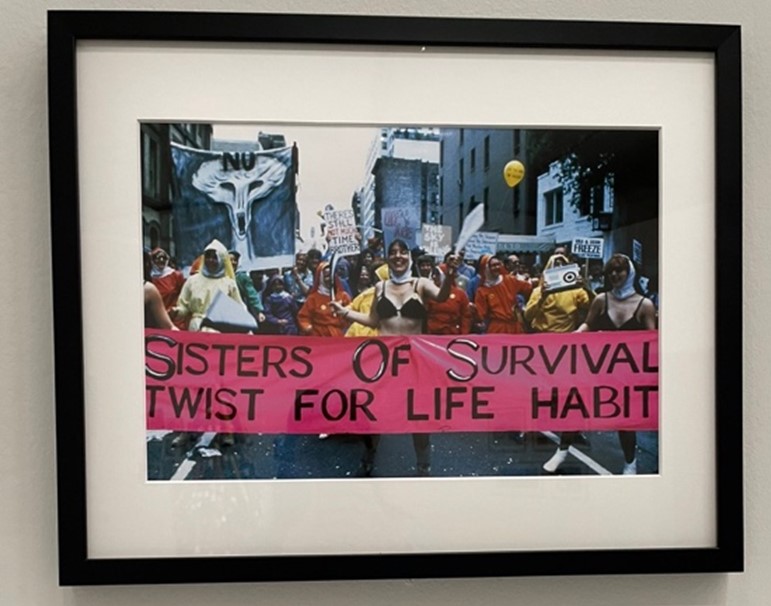

In contrast, with a big title, The Nuclearization of the World, a picture of some colorful nuns caught my attention. Sister of Survival was photographed at the 2nd United Nations (UN) Special Session on Disarmament in New York on 12 June 1982 (see picture 3). Jerri Allyn, Nancy Angelo, Anne Gauldin, Cheri Gaulke, and Sue Maberry founded Sisters of Survival, a feminist anti-nuclear performance group, in Los Angeles in 1981. They dressed as nuns in colorful outfits to symbolize their goal of a nuclear-free future and ideal diversity. Apart from Sister of Survival, there were also four series of photos from the Greenham Common Women’s Peace Camp in 1982, which similarly voiced their opposition to nuclear power.

This exhibition successfully portrayed women in various positions. From the examples above, I propose that peace and women must be viewed in conversation rather than as a black-and-white myth and position. Bringing back Ruddick’s book on Maternal Thinking Toward a Politics of Peace in conversation with my experience in the Nuclear Age Exhibition, I slightly added a point to her conclusion. She concluded that what connects women to peace is their maternal thinking rather than their biological gender.4 I agreed with her, but after reflecting on this exhibition, I would like to add that it is also about how they interpret ‘peace.’ Is there any good atom propaganda behind them? Lastly, do I not believe that women can commit to war? Rather than a direct answer, I prefer being skeptical, not instantly judging yes or no, and keeping an open conversation with any possibility of women’s position from various angles.

1 Sara Ruddick, Maternal Thinking Toward a Politics of Peace (Boston: Beacon Press, 2002), 143-147.

2 Petra Goedde, The Politics of Peace: A Global Cold War History (New York: Oxford University Press, 2019), 130-131.

3 Ruddick, 154.

4 Ruddick, 141-159.