by Floris de Ruiter

L’Âge Atomique was an exhibition held from 11 October 2024 until 9 February 2025 at Musée d’Art Moderne (MAM) in Paris. The exhibition makes you relive the nuclear anxiety of the Cold War through its art. Walking through the exhibition was unnerving but also gave me the opportunity to reflect. Although atomic anxiety seems currently on the decline, the idea of possible Armageddon lives on. As such, this exhibition acted as a mirror for me to reflect on the relation between artistic anxiety and mortality. The art of this exhibition helped me to contrast anxiety with pain and mortality with narcissism, gaining new insights into the relation between artistic anxiety and mortality. Atomic art uniquely prompts reflection on our relationship with death and, thereby, acts beyond the perceived temporal boundaries of its age.

Two concepts are crucial, anxiety and mortality. This exhibition shows how atomic art often reflected an interpretation of the instability of the human condition. During the Cold War, anxiety, the fear of an uncertain or unknown threat, was a constant presence. The instability of the human condition creates anxiety, anxiety can heighten a sensitivity to aesthetic vision. Thus, Cold War atomic anxiety held artistic potential. The second concept, mortality, well… it’s quite inherently tied to the reality of an atomic bomb.

First, I’ll discuss artworks in the exhibition that reflect atomic anxiety. One of the first pieces you’ll see is Barnett Newman’s Pagan Void, which highlights the artistic origins of this anxiety. A black gaping hole in the middle symbolizes the origin of emptiness from which terror and anxiety emerge in abstract forms. The description next to the painting effectively summarizes how artists valorized atomic anxiety into art: ‘L’abandon progressif des forms primitivistes et des références directes à la mythologie antique, l’expressionisme abstrait se fait au profit d’une abstraction sobre, capable d’exprimer “l’homme modern”, “ devenu su propre terreur” … la condition métaphysique nécessarie à la creation du Grand Art’. Newman’s painting primed me for the anxious depictions of Cold War instability that followed. Pinot Gallizio’s industrial art embodies a philosophy of ‘continuous destruction’ as the precondition for creative power. For an example, one need only look at his uncanny ‘Cavern of Antimatter’, with its ‘delirious mix of technological fervor and primitivist anxieties’.1

Jackson Pollock’s drip paintings similarly wield the atom bomb for the anxious abstractions of a volatile, alcoholic, psyche. After these paintings, I needed some rest and sat on a wall-engraved bench in the exhibition, when I suddenly heard Yoko Ono’s ominous Hiroshima Sky is Always Blue playing in the bench. Having put their differences aside, McCartney and Ono collaborated in 1995 on Hiroshima Sky is Always Blue to commemorate the U.S. bombing of Hiroshima. Besides the rather distracting peacock vocals of Linda McCartney, the anxious vocalizations of wailing and howling by Ono are concerning to say the least. My last example is Le Droit de l’Aigle by Asger Jorn, who himself grew suspicious of the true source of his own artistic anxiety. Here, ‘rage et anxiété mortelle’ are represented in chaotic mushroom clouds of ‘sovereignty’. Jorn stated later that these emotions could have only become such art because, at the time, he still believed in ‘la supercherie psychologique de la pretendue “Guerre froide”’.

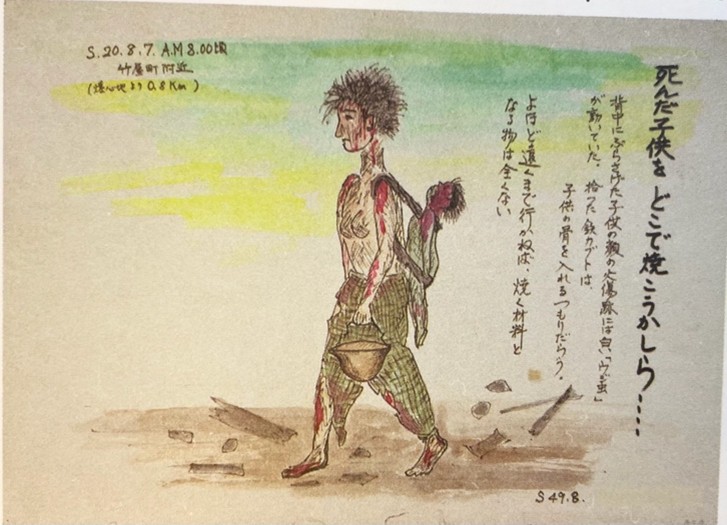

Contrasting this anxiety to the pain in Hiroshima testimonials showed me a difference between anxiety and pain in art. The ‘A-bomb Drawings by Survivors’ are artworks created by survivors of the Hiroshima bombing, collected in a campaign ‘to convey the Desire for Peace Across the Centuries’. It struck me as eerie that, although these direct testimonials were more horrifying, they seemed artistically less anxious or abstract. The transparent and concrete nature of hell on earth is reflected directly in the pain and desolation of survivor ‘art’. Chizuko Sasaki’s Corpses Floating in the River enveloped by fire looks like a living version of the Vaitarani or Styx with the pain of it all on full display. Similarly, Matsumuro Kazuo’s Mother Setting out to Cremate her Child shows the naked pain of grieving over the death of one’s child.

Anxiety for the bomb and pain by the bomb look different. The art of this exhibition puts the artistic dissimilarity on illustrative display. As such, anxiety and pain help us relate differently towards our mortality.

As the pain of Hiroshima testimonials is not mine and not for me to further comment on, my final remarks are on how I see the atomic anxiety of the first in an ambiguous relation to mortality. The anxiety in Newman’s Pagan Void, ‘“l’homme” “devenu su propre terreur”’, recognized a Cold War rupture in our relation to mortality. As a quote by Sartre on the exhibition’s wall recounts: ‘Apris la mort de Dieu, voici qu’on annonce la mort de l’homme … La communauté qui s’est faite gardienne de la bombe atomique est au-dessus du règne naturel car elle est responsible de sa vie et de sa mort: il faudra qu’à chaque jour, à chaque minute, elle consente à vivre. Voilà ce que nous éprouvons aujourd’hui dans l’angoisse’. Fear of the bomb became the Cold War way of facing mortality. However, the absence of God and presence of an omnipotent weapon seemed to put artistic anxiety into a stalemate.

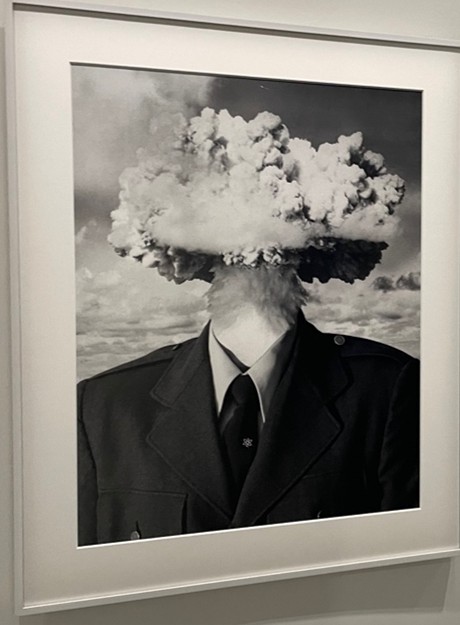

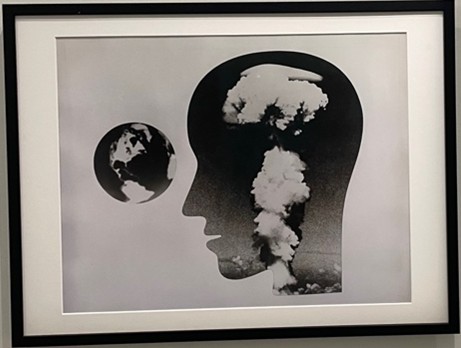

By definition, atomic anxiety could not resolve into a proper relation to mortality. It struck me that anxiety as the creative ‘condition metaphysique necessaire à la creation du Grand Art’ failed to fully unfold due to this defunct relation to mortality – never to rest in peace with Armageddon. As a result, under Sartre’s ‘l’angoisse’, one’s artistic anxiety either risked psychological disarray or an atomized narcissism obvious from the magnanimity of Gallizio’s ‘creation atomique’ of ‘l’homme nouveau’.2 The creator’s helplessness, caused by an uncontrolled relation to one’s own mortality, is clear in both Dali’s Nuclear Mysticism and the exhibition’s many Atom Heads.

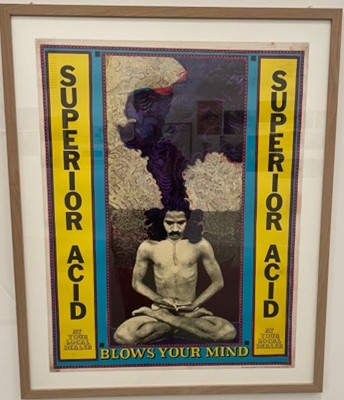

Bruce Conner’s Bombhead, Herbert Matter’s Atom Head, and the cover of Russel’s Common Sense and Nuclear Warfare, all bear a mushroom in control of the atomized psyche. Anxiety in the face of death that culminates in ‘une bombe atomique dans la tête’ – a self-centered trip of ‘superior acid’ that really ‘blows your mind’. Atomic art uniquely helps us reflect on anxiety’s relation to mortality. Upon seeing the ‘light of a thousand suns’, one cannot help but mistake ‘death, the destroyer of worlds’ for ‘the source of what will be’.3

1 Nicola Pezolet, ‘Spectacles Plastiques: Reconstruction and the Debates on the ‘Synthesis of the Arts’ in France, 1944-1962, (PhD Diss., MIT, 2012), p. 286.

2 Both are taken from quotes on the walls of the exhibition. Sartre’s quote can be found in Éditorial, Les Temps Modernes, Octobre 1945 and Gallizio’s quote in ‘Manifeste de la Peinture Industrielle. Pour un Art Unitaire Applicable’, 1959.

3 With some inspirational remarks by Robert Oppenheimer and Carolien Stolte, I wanted to make a point by mixing some Bhagavad Gita slokas, see Barbara Stoler Miller, The Bhagavad Gītā: Krishna’s Counsel in Time of War (New York: Columbia University Press, 1986), pp. 95, 98; James A. Hijiya, ‘The “Gita” of J. Robert Oppenheimer”, Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 144, no. 2 (2000): 123-67.